THESE TINY THINGS

by angeliska on August 9, 2024

Today, August 8th, 2024 it has been 38 years since my mother’s death, at age 38. It’s strange to think that now she has been gone for exactly as long as she was alive — and in the intervening 38 years without her here, I’ve had to navigate what it is to grow up motherless, as well as trying to heal many of the scars of longing and loss from our too brief time together.

In the past few years of my long exploration of grieving, I’ve given a lot of energy and focus to trying to figure out and tend to the wounds of my early years. In the past year, I’ve come to a new clarity about the deeper reasons why our relationship was the way it was, and with that new understanding, I have come to a place of peace and forgiveness for the things that I see now were really difficult for my mom, and likely totally beyond her control.

For over a decade now, I’ve been sitting in healing circles that have been a major part of my journey towards mending some very deep wounds, and my own spiritual growth. These experiences have been incredibly humbling and often extremely challenging — but always ultimately very worth it. Not only I have received profound truths that I do not think I ever could have accessed in any other way, but also for the ability to move trauma through my body, connect to the divine, and be supported and witnessed in my healing by a loving community. Working through my developmental trauma has given me the capacity to delve into the serious “Big T”, or shock traumas I went through as a survivor of stalking and violent crime, as well as being a climate refugee, displaced by Hurricane Katrina. I am in the process of writing a memoir about going through those heavy things, and am still trying to figure out where the writing about my mom fits into all that — or if these writings need to be their own separate book.

Over the years, in the writings I have done about grieving my mother, and our short (and often disconnected) relationship, I’ve alluded to the visions I’ve received while sitting in these spaces (and occasionally on my own adventures in nature) — but tend not to go into great detail about them for reasons related to privacy and legality, as well as a desire to keep those experiences sacred. I will continue to keep my descriptions intentionally vague — but I don’t know any other way to explain how I got here, and I don’t want to make it seem like any of this massive transformation that has taken place over many years, was just happenstance. It truly wasn’t. I had participated in many rounds of talk therapy — since childhood, throughout my adolescence, and into adulthood for my intense fear of abandonment and persistent anxiety, to no avail.

I have come to understand that whatever the medium or conduit for awakening and revelation, some truths will not be handed over to you until you’re really ready to receive them. It’s possible that they tried to come through in other forms and fashions, over the years — but I just couldn’t comprehend what they meant. I didn’t have the language for any of it, or I just wasn’t ready to hold it. This past November, it seems I was finally ready to unlock a bigger piece of the puzzle — but that unfolding took many hours, and countless tears.

The revelation was this: most of the people in my family are not only just somewhat neurodivergent (I’d known or suspected this for quite a while), but actually autistic. My mom was super fucking autistic. And so am I.

It’s immediately confronting to write about this, because of all the doubting voices in my head that chorus, “So, what’s your proof?” or “What right do you have to claim that?” and “How would you know, without getting a proper diagnosis?” But the thing is — it’s exactly those voices (which are plentiful in real life, and on the internet, unfortunately) that have led to so many women and assigned female at birth folks going years and years (or their entire lives, or never) without knowing this essential truth about themselves. It’s true for male and AMAB people too, but they are SO much more likely to get diagnosed, and not fall through the cracks in the way that girls who are socialized to perform care and attention in specific ways are. Being a highly masked autistic person is its own special kind of mindfuck, and honestly it just boggles my mind that it took me this long to finally see it.

The truth is, this is something I’d been questioning for many, many years — but it wasn’t presented to until I was truly ready to grapple with the reality of it. And when I finally saw it, I couldn’t stop weeping. Not because I was distressed at the realization, but because I’d wasted so much time and caused so much unknowing harm in my commitment to misunderstanding so many dear people in my life. So many beloved friends who’ve I’ve knocked heads with over the years, family members who I relentlessly pathologized (trying to figure out what their fucking PROBLEM was) — and not least of all myself.

I won’t discuss the particular peculiar peccadilloes or habits of anyone else still living in my family or friend group, because that’s their business, and I do get that armchair diagnosing people isn’t really the thing — but during one night, I witnessed such a wild cataloguing through a myriad of arguments and conflicts with people who I love and I know love me… and could finally see that it’s just that our ways of being super fucking autistic have often been at odds, and we didn’t know it (and definitely didn’t know how to talk about it). So many hurt feelings, misunderstandings, and miscommunications — often resulting in years of silence and estrangement.

The combined issues of rigidity around plans and routines, sensorial/overstimulation needs, inflexibility in personal views, and sometimes a difficulty expressing empathy and reciprocity (or in my case, demanding that those things be expressed explicitly, and in a certain way!) has led to me coming to impasses with far too many people I’ve loved… But there’s something about that way neurodivergence is often either totally invisible or completely demonized and misunderstood in women that has made it so difficult to understand all these years. After all, it’s easier to just think, “God, what’s HER problem? She’s so controlling/spacey/oversensitive/dramatic/unreasonable/crazy!” My heart breaks to think of all the women (and of course people of all genders) who were deemed insane, or monsters, or worse — because they weren’t able to mask and hide hard enough.

Even worse, there have been friends and loved ones who have come to this realization long before I ever did — but I pooh-poohed it. Not to their faces, usually — but yeah… I’m heavily ashamed of myself for doubting their autism — but to acknowledge their truth would have meant reckoning with my own, and everything it meant… And I simply wasn’t ready to do that, until it was lovingly shoved in my face by a power much greater, more ancient, and infinitely wiser than me.

Now, to be clear — I’m not blaming all my issues in relating on mutual neurodivergence, but… the reality is that most of the time I just couldn’t see it, because it’s the water I’ve been swimming in my entire life. I never thought I was neurodivergent, because I was surrounded by a majority of neurodivergent people in my family of origin, and have attracted and bonded to probably mostly fellow neurodivergent people throughout my life.

In talking with my dad about this, he confirmed a lot of what I’d wondered about for a long time, and as we compared notes, he also told me that he believed my stepmomma Karen was also highly neurodivergent (and likely also autistic). I have so much to process around her death, and our relationship as well. The one year anniversary of her passing is coming up, on August 26th (three days before the anniversary of Hurricane Katrina), and now August is such an emotional tinderbox of a month for me, I’m starting to wonder if writing will even be enough anymore. I might just need to go into an actual cave every August, from here on out. I miss Karen so much, and have been dreaming about her more, as the day of her death approaches. In the last one, I was hugging her, saying, “I don’t want you to go!”

I wish I could talk with her about all of this – wish she could read this piece, as she often used to. There are so many things I would ask her, about her own experience. I wonder what she would think about these ideas, and if she would see it in herself, and in the rest of our family.

Honestly, it’s hard to imagine a severely neurotypical person being able to really handle (much less fully embrace) the eccentricities of just about anyone in my extremely unusual family. But I was so used to everyone’s weirdness growing up, I honestly just didn’t think anything of it. It took me a long time to comprehend that all our hyper-focused special interests, stims (both subtle and intense), dietary obsessions, and social awkwardnesses was more than just us being your average familial group of oddballs.

The bottom line is that I don’t give a rat’s ass if you believe me or not, or if you’re offended by this supposition, or think I’m delusional for believing any of this about myself or my family. It’s scary to put it out there, and to imagine being doubted or judged — but in the end, what you think about my life or my process really isn’t any of my business, and…the fact that you’ve read this far may mean that you’re staying with me in this so far (and for that I thank you!). I’m so heavily conditioned to the self-doubt, that I completely internalized it…So being able to share about any of this publicly is me pushing against that. It’s not easy, at all. It’s taken me a very long time to write this, and I’ve gotten up and walked away from it, over and over — convinced I couldn’t do it, wouldn’t find a way to say what I needed to say here. But this is me trying.

When I wrote about my relationship with my mother the year before last (HAZY WINDOWS, in 2022), I was in a lot of pain. I was navigating a lot of hurt and anger at how emotionally neglected and rejected I’d been, and the lasting trauma that has given me to work through. And that writing was part of that healing process for me. It’s all still true — but I just know more now. I understand why it was like that, in a way I simply could not see at the time. In that piece, I describe myself as being ADHD and HSP (Highly Sensitive Person), which was my diagnosis at the time. I realize now that HSP is not actually an official or actual diagnosis, and in fact I think that it’s actually just…girl autism.

When I received my evaluation for neurodivergence, I went in thinking there was a pretty high likelihood that I’d discover I was autistic. But the evaluation was given online, over Zoom and self-guided, with very outdated testing materials that were clearly designed with male people in mind. The psychiatrist who led my eval was not neurodivergent herself, and did not perform any kind of thorough testing outside of what I received, which was mostly lists of questions you had to answer on a scale (with 1 being not at all likely, and 5 being highly likely, etc.) though that kind of scoring system has been shown to confound autistic people. In the end, she said I was definitely ADHD (inattentive type), and though I had many of the characteristics of an autistic person, I just “didn’t rate high enough on the scoring” to be diagnosed as such. I took her word at gospel, and decided that she knew more than I did on the subject.

It was confusing, but in some way I was relieved — because it meant that the friends I had confessed my concerns about possibly being autistic to were right, too. They told me that there was no way I could be autistic, because I was too empathetic, and too adept socially to ever really be on the spectrum like that! At the time, I didn’t really understand how the whole spectrum thing worked, I didn’t know what it meant to be highly masking, and I didn’t get that you can very much be both super ADHD and super autistic. Or that one of my main special interests has always been “humaning”, as in — figuring out how to human adeptly, vis a vis: expressing emotions in expected and acceptable ways, establishing healthy and long-lasting emotional connections, doing manners and social cues correctly, and understanding how interpersonal relationships work.

Grappling with this self-understanding has been incredibly powerful — especially seeing all the odd little quirks and struggles I’d just chalked up to being a weirdo among weirdos. It’s also been really painful at times — thinking of how long it took me to accept these things about myself, and not harshly judge myself for things that I really had very little control over. I’ve had to grieve all the years where I felt like a total alien, constantly observing others on how to act, how to talk, or respond — and always worry that I wasn’t convincing anyone. Wasn’t doing it “right”. And then there’s the intensity of unmasking, and of skill regression. It’s been an odyssey unto itself, and one that is still unfolding. I hope to be able to share about it more, because despite the stigma (and potential hazards) around revealing one’s autism publicly — I think it’s far more worth it to be open about who I am, and why I’m like this.

In reading and learning as much as could in the past year, so much has come to light — especially about the vagaries of mothering while autistic. Suddenly, so many of my difficulties with my mom make perfect sense. I can see now how utterly overwhelmed she was, on a sensory level — by the physical reality of an infant, then a toddler, and then a young kid. The constant need for touch, the stickiness, the high-pitched noisiness, the messes — I know she struggled immensely with all of this. Reading and witnessing accounts from autistic mothers grappling with the shutdown a screaming toddler could bring on, or the rage from seeing a room you just set to rights immediately turned into a disaster zone by a pint sized tornado gives me so much more compassion for what my mom was dealing with, and helps me understand how much it all goes beyond typical “parenting stress”. It is majorly intense, and can be totally debilitating.

I can remember viscerally the feeling of her pulling away from my grasping little hands with revulsion, almost shuddering from my touch — when all I desired most in the world was to be close to her, to be held, and comforted. To be wanted. I’ve been honest about all the ways that experiencing that from her repeatedly fucked me up. And I also know that it wasn’t always that way, between us. That there were times when she had the capacity for tenderness, and was able to give me what I needed. I just think it was tricky for her to do it consistently, and especially when she was under stress and duress — which was often during those years of financial hardship, overwork at shitty low-paying jobs, chronic pain and terminal illness. But so much of that pain is soothed and healed in finally understanding that it was never about ME! It wasn’t because I was revolting or fundamentally unlovable! She was just extremely overwhelmed, in a very particular way that is super hard for autistic moms (especially when they don’t know they’re autistic!)

I can have so much more compassion for my child self now, too. That kid was just so confused and hurt and lonely. All I wanted was to connect with and be close to my mom — but I was hyper-aware from a young age that there were rules to engagement with her, and that it really had to be on her terms. I was left to my own devices, a lot — and given headphones to wear to watch my cartoons, at a time when that wasn’t common or very accessible at all. It still hurts — but so much less now that I know it really wasn’t my fault. Or hers. We were both doing the best we could, with the tools we had. And there was so much we just didn’t know about ourselves, or one another.

When I was finally ready to see all of this, to truly know it on a soul level, it was incredibly humbling. I was brought to my knees by the all this truth — quite literally floored by this now extremely obvious thing that had been staring me in the face this entire time. I just wasn’t capable of understanding what it was, until now. It felt like being gently guided toward a mirror in which I could at long last see myself clearly — and behind me, was my mother, gazing into my eyes over my shouder. Her hands pointed backwards, towards all our other family members and ancestors who dealt with this same combination of hypermobility/connective tissue disorders and neurodivergence. I recognize what a blessing it is to be born into a time where at least I am some answers for why my body and mind are so different, and often so troublesome. It was a earth-shaking experience for me, and one that has changed my perspectives of reality utterly.

I’m going to get reevaluated for autism soon, by someone who understands much more clearly and intimately how it’s represented in women and femme-folk. I’m grateful to have access to multiple levels of support, much more awareness, and a lot more in the way of accommodations. My health insurance blessedly covers therapy (my therapist also has AuDHD), and this new evaluation (they are generally quite expensive). My mom didn’t have anything like this, and I don’t know if she’d lived, if she’d even be open to contemplating any of this about herself. It’s a lot to sit with.

Maybe it’s nuts to apply this diagnosis retroactively to a dead woman, but look — the truth is that it explains SO MUCH about who my mom was. She had lifelong obsessions with certain artists and musicians (particularly Hank Williams) that went beyond mere hobbies. They were her special interests, and she leaned into them hard. It’s not surprising that she found similarly hyper-focused friends who had the same special interest, and would get together with them to fixate about every detail of Hank Williams’ life. It’s funny — I could see the autism in many of them, much earlier on…but they were men. It was more obvious, or more acceptable, or…something. Mainly, again — I think if I acknowledged it in her, I would have to start acknowledging it in myself. And it was easier to think of her as seriously eccentric, or maybe even a bit crazy. So many of the habits my dad described to me sounded like OCD, depression, or neuroses — but I now see them for what they really were: aspects of autism.

One of her big stims was trichotillomania — picking her hair out until a bald spot formed. Mine has always been hair twirling (one of the main reasons you rarely see me with my hair down — I’ll play with it compulsively) and finger skin picking. It’s taken me a long time to not feel intense shame about these things (both in myself, and in my mom) — because it was always treated as evidence of mental illness or neurosis, rather than than coping mechanisms that are directed inward. Much stimming behavior for women is well-hidden, body-focused, and self-harming — not because we want to hurt ourselves, but because it’s less noticeable and disruptive than what men and boys can get away with in public (drumming on the table, shaking their legs, being overtly hyper or aggressive). All that pent up energy has to go somewhere — and for us, it was always focused on ourselves, because usually no one would be bothered by that (even if it hurt us).

My mom was extremely controlling and exacting about her home and personal environment — she couldn’t abide sticky messes, and popsicles were strictly prohibited indoors. She couldn’t tolerate things that were even slightly broken or messed up. Those items would disappear into the trash overnight, even if they belonged to me or my dad. She could often appear affectless, and what I think I once interpreted as depression or “resting bitch face” might have been her just… not masking, or forgetting to make a facial expression. Or just thinking intently, lost in her own world. I recognize that in myself.

Regardless of how I got here, or how long it took me — I finally have so much more peace than I’ve been able to access, really ever. That peace, understanding, and compassion is extending outwards too — to other people in my family and friend group who’ve driven me to distraction because they just won’t do empathy in the “right way” that I want them to (not info-dumping on me about their own lives, asking me questions about mine, remembering to show care in certain ways, and on certain days.) And strangely, as I’ve become more understanding and forgiving, they’ve become more responsive and available for showing me kindness and care in the ways I’ve long wanted and needed. Funny how that works, isn’t it? I’m more patient with myself, and more patient with those around me. I judge myself and others far less harshly, now that I can see what our “deal” is. Don’t get me wrong — I still forget sometimes, and get irritated and frustrated with all of us…until I remember why we’re like this, and what it takes from us to have to pretend to be any other way.

I wrote this piece earlier this year, in the wonderful memoir class I’ve been taking. The prompt was “Things that are too small to mention” — and it’s about what all of the above actually felt like, in my lived experience, as a child (at least in part).

These Tiny Things

The little girl is lying on her mother’s bed, rubbing her big toe along the satiny ribbon that divides creamy sections of tea-rose printed wallpaper. It is immensely satisfying to feel the smooth glide as she draws her leg upwards, with her toe tracing the shiny silken line, alongside the coral-pink roses twining towards the ceiling.

It feels like sharp scissors sliding through cellophane tape or laminate. Like when she’s sometimes allowed to help her 1st grade teacher trim the posters for the classroom walls. That shivery rushing glide through clear plastic, and the delicate strips of cellophane falling gently into the wastepaper basket is really the best part about going to school — but it only happens every once in a while, and only after she’s finished all her reading assignments, and after she’s helped the kids that are struggling with their reading.

Reading is easy, though. At four years old, after becoming immensely frustrated one evening when her parents were both absorbed in their books and not paying attention to her, she decided she would learn to read, too. She scrambled into her father’s lap and gazed intently at the page of wriggling black shapes that seemed to be so fascinating to him. It made no sense, no matter how long she stared — until one day, when he was reading Hop on Pop aloud to her, the words clicked into place, and she understood the secret language, finally.

As soon as her father tracked that she was starting to get it, a book of boring bible stories became the bedtime ritual. She pretended to stumble over the incomprehensible tales of Job and Adam and who begat who until her father became distraught, fearing that she would never become an avid reader…

Meanwhile, she was sneaking Old Yeller off the shelf, and reading ahead — since they only read one chapter a night, and she wanted to know what happened. When she got to the tragic ending, she had to cry in secret — and pretend it was a surprise when her dad read it to her the next night. Eventually her ruse was discovered, and she was able to choose new chapter books over bible stories, and sit in her little rocking chair reading books contentedly with her parents in the evenings.

Her teacher says they’ve run out of textbooks for her to read, and they’ll have to ask the nearby middle school for some 6th, 7th, and 8th grade books to keep her busy. Until then, she’s sent to the remedial room to help tutor the kids who aren’t reading well yet. Her friend Debra’s parents were told that she’d probably never learn to read, but after a few weeks of patient trying together, that proves not to be true. They are so overjoyed that they give the little girl a brass bracelet in a velvet box. It turns her wrist green after a while, but it’s very special, so she wears it every day anyway.

Math is not easy. Numbers are confusing, because they all have a color and a personality, but no one else seems to know that. The magnet numbers and alphabet letters on the refrigerator are all the wrong colors, but her parents don’t understand when she gets mad because they’re all switched up. Who would do that?

Everyone should know that two is a just a little baby and always yellow, and three is a kid and true blue. But when added together, they should make green (who is four) but instead apparently it makes five (who should always be red and has freckles)! So addition and subtraction get very confusing.

She tries to explain this to the teacher, but for some reason, this is very irritating and she’s told to go stand in the corner until she’s ready to stop being silly and do her math worksheet properly without telling stories. The colorful number people were once her friends, but now she feels betrayed. She doesn’t know that it will only get harder and harder — or that dyscalculia, hyperlexia, ordinal linguistic personification and synesthesia are all aspects of her neurodivergence that she won’t come to learn about or understand for at least four more decades.

The wrongness of things tugs at her, and she can’t let them go. The way adults don’t say what they mean, or get angry when she does. The way the old cat scratches her when she doesn’t pet his fur in the right direction, and the way his whiskery tongue grabs at her fingers when he licks popsicle juice off her hands. She’s not allowed to eat sticky things inside the house because stickiness is very wrong for her mother, who also can’t stand it when things are broken or damaged in any way. The things disappear quickly after that, even when they’re still good, or beloved. Often, it’s her favorite toys that have to go. The flock of butterfly stickers she lovingly applied to her vanity mirror made her mother have to go lie down in a darkened room — but they got to stay, because pulling them off would just make more stickiness.

She has to be very, very careful when mixing and pouring the purple Five-Alive from the frozen can into the tall blue aluminum pitcher, and then into her aluminum tumblers, all metallic jewel colors. They sweat down the sides in the heat, and become frosted with silvery condensation for a little bit, and you can trace little designs on them with your fingernail. She likes to pretend the punch is red wine, and will be very elegant sipping it as she sits too close to the television playing Sesame Street. She likes to be fully immersed in the psychedelic close up scenes of ocean waves and crayon factories and children dancing to funky songs.

You’re not supposed to sit so up close to the TV screen, because you’ll damage your eyes, but since she already has to wear thick glasses anyway, it’s probably okay. No one is around to tell her to move back, so she can do it this time. More and more, her mom is in her room laying down, not feeling good. So she can watch as much television as she wants, and mix her own Five-Alive, as long as she doesn’t spill and make a mess. Eventually they’ll learn that those aluminum glasses are dangerous for your brain, but for now, they’re the fanciest ones she’s allowed to drink out of.

Underneath the cedar table they eat dinner at is a secret world no one else knows about. She can hide under there and inspect the spiders’ eggs that look like miniature cotton balls. She wants to collect them and pet them, but she’s not supposed to touch them at all, because she might hurt the baby spiders inside. They’re all Charlotte’s babies. Spiders are good, and friendly, and write words in their webs when they want to. The eggs are so soft looking, but the idea of hundreds of baby spiders pouring out is both exciting and horrifying. She waits a long time under the table, watching to see if it will happen, but it never does. Maybe they’ve already hatched, and if so, surely it would be okay to take some into her doll-house in her bedroom? But what if she’s wrong and they hatch in there and crawl all over her face while she’s sleeping? Better not. The spiders are something she loves, but also so many of them all rushing at her makes her want to throw up and take her skin off and run away.

The little girl is still contemplating all this wrongness when she drags her toe down the wallpaper the other way — so it pulls at her skin when she slides down, the opposite of the sweet smooth gliding. Why can’t it be smooth both ways? It doesn’t make sense how touching it one way can feel so good, but the other way feels so bad. But she has to always go up and down, for some reason. Not just up. There are lots of rules to these sensory explorations, but it’s not clear who decided them. The little girl is laying on her mother’s bed, touching the wallpaper with her feet (which isn’t allowed — it’s only supposed to be touched with her hands, and only when they’re not sticky), but her mother isn’t in here at the moment. The little girl’s mother is at the doctor’s, or maybe at the hospital, and she’s very, very sick.

The little girl is aware that she’s narrating everything that happens to her, even the really big upsetting things (especially those) in this third person way, even though she doesn’t have the language for that yet. But she knows it’s a weird thing to be doing, and senses that other kids don’t really think about themselves in this way, or maybe at all. She wants to stop it, but she can’t, and that feels even more upsetting. She sits up on her knees and bangs her head gently against the wallpaper a little bit, hoping to re-set her brain, thinking furiously, “No! I AM the little girl! The little girl is me! This isn’t a story! It’s real life, so start acting like it! Just act normal!” But it doesn’t work for very long, really.

Pronominal reversal is pretty typical in thought patterns and language for autistic children, but the little girl won’t learn about that until reading about it today, when she’s 45 years old, and doesn’t even identify as a particular gender. There will be so much more understanding, and so many more options, eventually. But for today, she’s only six, and there’s just the ceiling fan spinning above her — around and around, making the frosted glass lights fixtures wobble. She likes to imagine being able to float up to the ceiling and walk on it like upside down world. Maybe then she could talk into the ceiling fan to make her voice go all robot-y like the metal fan that blows the white Swiss dot curtains her mother sewed. The fan on the ground always has to be angled towards the windows, because her mother can’t stand having any kind of wind blowing right on her. So the little girl always has to remember to turn it back the right way after talking into it and making her voice sound like paper folded up accordion-style. It makes her whole body feel funny and she can lay on the cool linoleum of the floor and tell secrets into the fan for a long time, as long as her mom isn’t trying to nap.

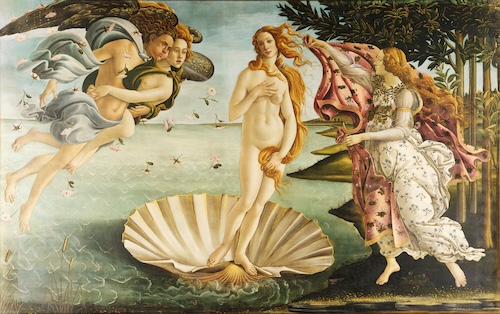

Her mother’s bedroom is a forbidden and sacred haven of visual and sensory delights — and a place where she can feel close to her, but usually only when she’s not there. It’s okay though, because even when she’s away, she’s still there somehow — watching from the framed prints on the wall of naked women whose pale bodies are the same shape as her mother’s. It only makes sense that these would be paintings of her mother, in different guises.

The one above the bed, hanging right over the best spot for toe-touching the silky wallpaper ribbons, is her favorite. It shows her mother standing in a shell in the middle of the ocean, with her red hair extra long, twining around her white limbs. Her face is gentle and half-smiling, even though she’s flanked by angels who seem upset that she’s naked, and an angel who’s blowing wind at her with an angry face. Her mother won’t like having wind blown at her — but in the painting, she seems serene.

In the other painting, her mother is sitting naked on a picnic blanket, looking out at the viewer calmly. She’s sitting with two men, one who must be her father, and the other is maybe an uncle? There’s another lady in the background who might be her Aunt Ruth. They’re all outside, in the woods. This painting is somehow scandalous, where the one of her mother in the big scallop shell isn’t, even though the angels are rushing to cover up her nakedness. Sometimes her mother walks around naked and disoriented, looking for her pills, and her dad gets upset when she walks by the sliding glass door and herds her back into the bedroom to lay down.

Years later, when the girl is more grown and traveling, she will see these paintings in museums, and feel shocked at so many other people admiring these images she grew up thinking were pictures of her mom. How dare they ogle her mother like that, naked in public? When for so long, they only existed in the private realm of her bedroom sanctuary… And how did Botticelli come to paint her mom in the Birth of Venus, and when did she model for Édouard Manet in Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe?

But for now, the girl is still six, and her childhood exists in the perfect bubble of this dreamy, pretty room filled with art and everything her mother treasures. She doesn’t know that she is one of those treasures, too — because it’s hard for them to connect, when their needs are so different. Her mom needs a lot of quiet and for everything to be pristine and beautiful, and to not be touched with sticky hands. And the little girl needs to be held, with open arms, and gazed at lovingly, and played with and sang to and to not have to wear special headphones when she watches television so it doesn’t bother her mother. To not be left endlessly alone to occupy herself with books and shows and toys until none of it is fun anymore and she’s so lonely she cries in her periwinkle twilight blue bedroom with the sun making rainbows dance all around her.

She doesn’t yet know that a year from now, her mother will die of cancer, and they will never get to know one another beyond this time, and these ages. They will never get to have a conversation about their sensory particularities, and all their special interests, and what it is to be autistic your whole life and not know it until much later, or to never know it. But these tiny things live on. The pleasure of touching certain fabrics and textures, or imagining the upside world, or even sometimes finding a fan to talk into.

That crappy little house on the dead end street in the small town where she lived until age seven still stands. It was too tiny, pre-fab with cheap aluminum window frames — but her mom managed to make it all so lovely, with very little money. Those handmade curtains and chandelier crystals making prisms in the windows. Crocheted aprons pinned to the walls, and beauty everywhere you looked. They moved away after her mom wasn’t there any more to keep the magic in it alive.

The kindly lady who lives there now let her in to look around one rainy afternoon, a few years ago. There was nothing beautiful left in the house, no remnants of her mother, or her childhood — except for that magic wallpaper with the creamy ribbons and the pink tea-roses, still there in her mother’s old bedroom, somehow, decades later. The little girl, now grown, stood touching it — first up (smooth-smooth-smooth) and then down (rough-rough-rough) for just a moment, remembering.

If you’d like to read more about this journey

of grieving, honoring, and remembering

my mother on her death day,

here is an archive of my writings about her:

THE WIZARD’S JAR

HAZY WINDOWS

THE AUGUST RITUAL

FALLING STARS + CACTUS FLOWERS

DOUBLE ETERNITY

MY ANGELIC INHERITANCE / THE HOLOGRAPHIC WILL

38 ON AUGUST THE 8TH

30 YEARS – SEIZURES

888 – HONEY BABE, I’M BOUND TO RIDE – DON’T YOU WANNA GO?

WILD BLUE YONDER

NO ROOM IN MY HEART FOR THE BLUES

FAMILY VACATION – HANK WILLIAMS’ GRAVE

STAR-CROSSED TROUBADOURS

Foxes in the Rain

Triumvirate Lemniscate

Gustav + Mama – August 8th

And if any this resonates with you, here are some resources that have been helpful for me in understanding more about autism in myself, and in my mama:

Leave your comment